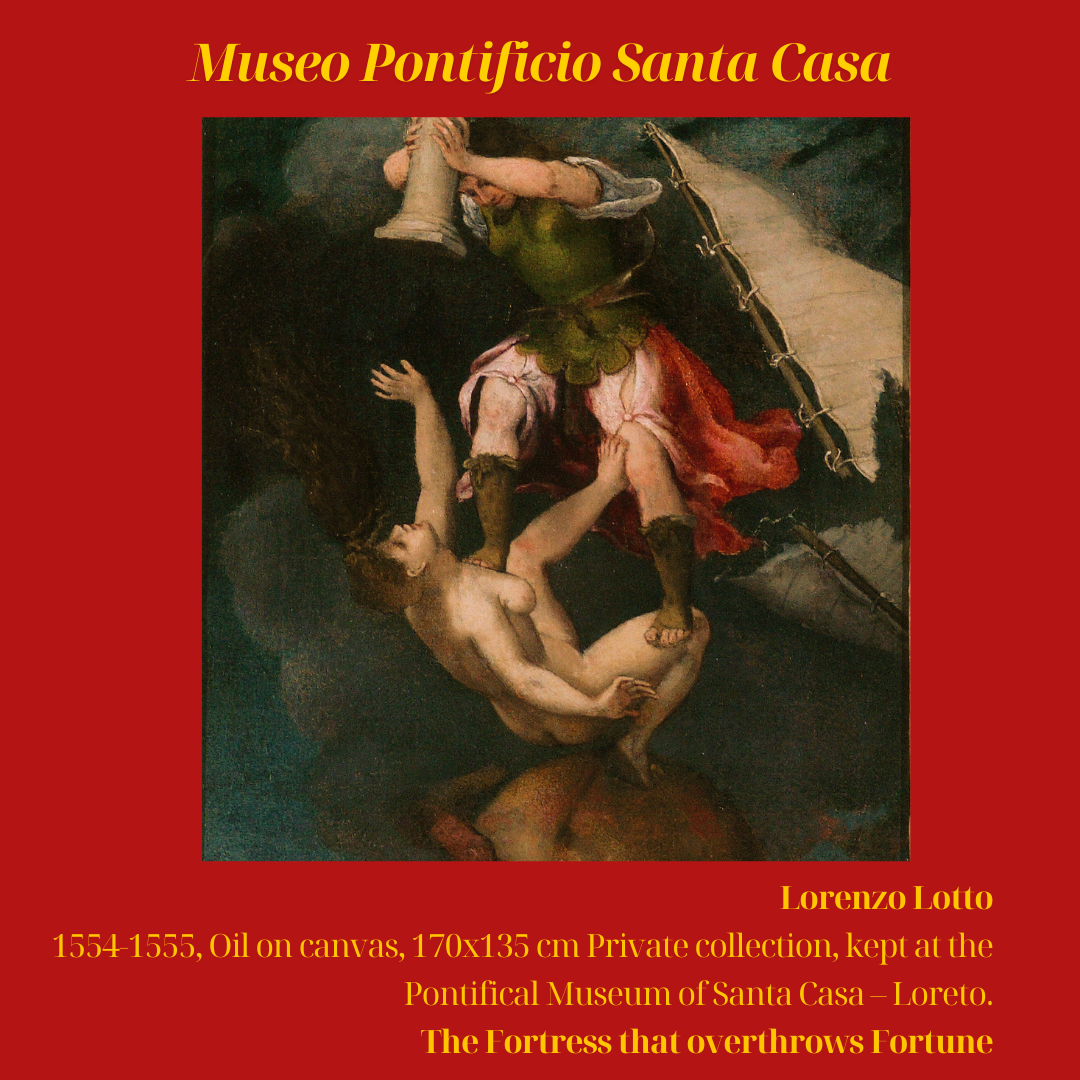

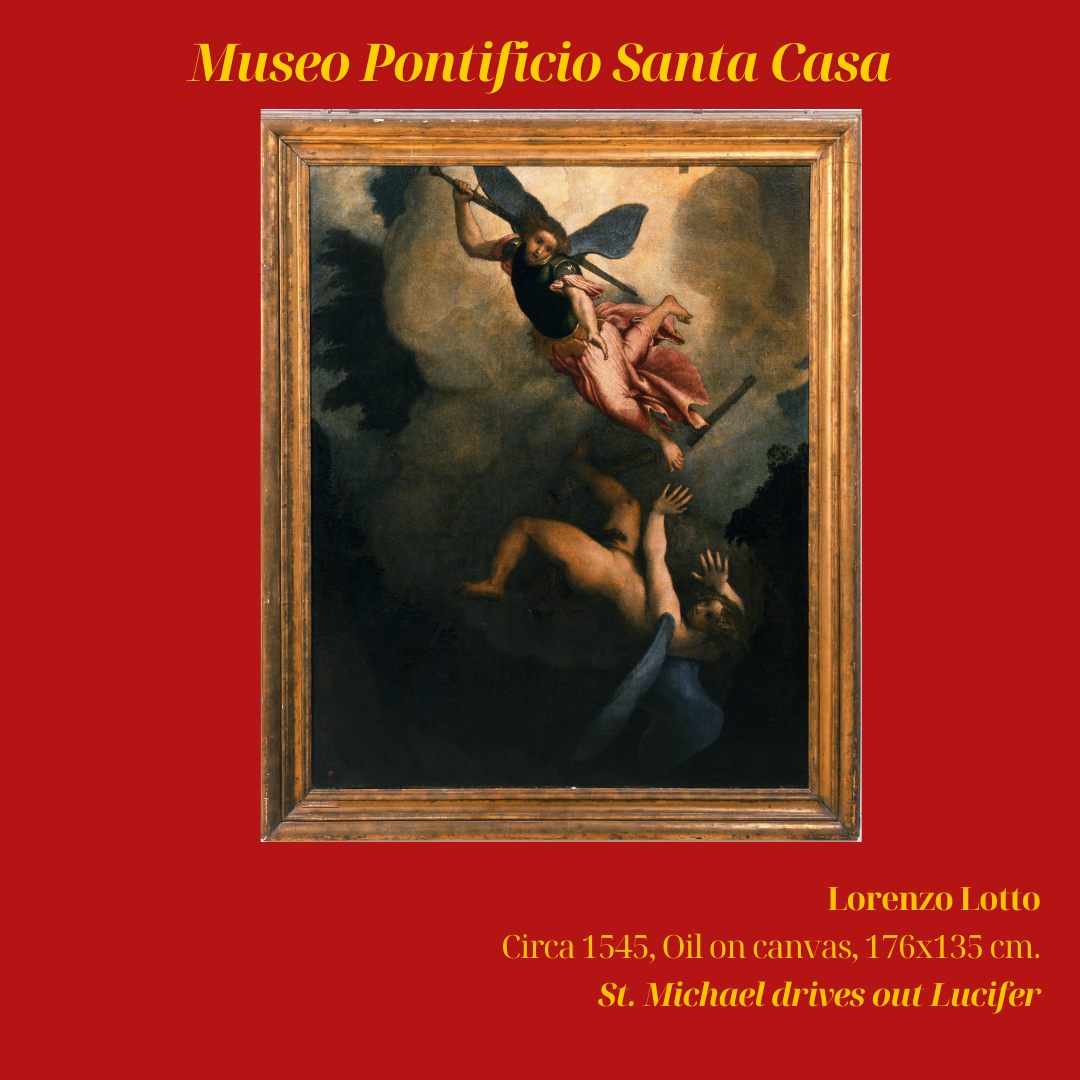

Defined by Lotto himself as an “altarpiece of a St. Michael beating and driving out Lucifer” the painting depicts St. Michael the Archangel, wrapped in the glow of a cloud illuminated by divine light and in the apparent act of “driving out” Lucifer in an abyss of darkness (the struggle between the two is mentioned in Revelation 12:7, as well as in Isaiah 14:12,15, in Jude 6 and in 2 Corinthians 11:14). From the ephebic forms, the fallen, or rather, the “falling”, has nothing monstrous traits with which it was previously depicted and which will characterize it later. The Lottesco Lucifer is a true unicum. It shares traits of Michael’s features. And the skin is lucid, angelic, because it is still reached by the light. Even with his sword raised and intent on breaking the stick of the decadent nude, Michael seems to make an extreme gesture of charity: the offering of his left hand is as if to draw Lucifer to himself, as if to make of himself an instrument of salvation. Even the nudity, the twisted tail and the open hands in a gesture of extreme defense seem to indicate a destiny by now marked and chosen. There are clouds, leaves, bushes, and cliffs, apparently giving it a natural context, an exterior landscape. However, a perfect resemblance between the two figures and the symmetrically drawn gestures suggest the unfolding of a struggle and a charitable gesture in an interior place – an inner sky. In that cloud, which so much resembles a heart, there is the instant of choice, of freedom – either Light or darkness, good or evil. In the instant set by Lotto on this canvas, there is the indissoluble coexistence of good and evil inside the cloud-heart.